A Runway Walk Through Fashion History

By Jonquil O’Reilly

As a fashion historian, I can’t help but view contemporary clothing through an historical lens and compare trends and sartorial choices to those from centuries past. With “fast fashion” so immediately available today, we’ve largely lost sight of the time, skilled craftsmanship and sheer expense that would have been required for the production of clothing before the modern era. Prior to the invention of the mechanical loom in 1785, and the sewing machine in 1830, fabrics were woven manually and clothing was sewn by hand by tailors sitting cross-legged on the floor. Clothing had to be durable and was expected to be reused.

Garbagia’s ensembles, brimming with CAUTION! tape ribbons, high-vis panels and traffic cones, were a stark reminder of how disconnected we have become with the processes of clothing production. In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, clothing for society’s most elite wearers was reused and repurposed again and again. Monarchs and high ranking members of the nobility would gift their worn gowns and suits to other courtiers or staff. As the clothing became stained or damaged by wear, they would be unpicked and reworked – velvet gowns might be patchworked into ecclesiastical vestments, or used to cover kneelers for church pews. They would eventually be cut up and sold on to the rag trade. Every inch of valuable fabric would be used up.

For those with means, dress was all about show – displays of wealth, of power and of social standing. In the 16th century, women wore stiff gowns with voluminous, conical skirts. Their vast circumference allowed them to display reams of sumptuous cloth, often heavily brocaded or weighed down with embroidery and applied decoration. The sheer size of Ankon Mitra and Piyusha Patwardhan’s Inhabiting a Fractal Pyramid reminded me of these gowns, taking up space on the road, the sidewalk or, indeed, on the stage at the festival’s Paper Dress Ball. It demanding to be looked at and admired. The cut-outs in the pyramid dress recalled the trend for “pinking” and “slashing” in the 16th and 17th centuries, in which fabrics were decorated with slits to reveal multiple layers of expensive textile beneath. The size and stiffness of these clothes altered the way women walked and moved. These large-scale skirts not only had an imposing presence but they acted almost like a guarded parameter that kept others at a physical distance. Certainly no one was getting close to the wearer of that pyramid dress.

These structured garments obliterated the natural form of the wearer. Large skirts were supported underneath by farthingales, stiffened, hooped underskirts that were sort of precursors to the familiar 19th-century crinoline. Any hint of a leg or its movement would have been considered indecent so these underskirts kept the lower half of the body hidden. These farthingales jumped to mind immediately when I saw Layers of Exuberance by Kaczmarek/Miranda. Like those farthingales, this piece encased its wearer at the centre of its massive circumference, giving no sense of their natural shape and acting like a surrounding forcefield. The rise and sway of it as the model walked made me think of Spanish women wearing the guardainfante skirts, immortalised in Velazquez’s Las Meninas, who clung to the fashion long after the rest of Europe were wearing (relatively) slinkier skirts and whose hips would bob distinctively as they walked.

For men, fashions were often inspired by armour and battle wear. Clothing was padded which cushioned the often crushing weight of chainmail and breastplates – something Alex Bard would know all about after many hours wearing his spectacular Featherman. While his birdlike silhouette seemed about to take flight, the steel feathers and chainmail weighed him down. Though it could be utilitarian, padding was more often used to sculpt the body of the wearer. 16th-century men wore padded doublets (a sort of button-up jacket top) with heavily padded fronts which pulled back the shoulders and thrust out the chest. These often mimicked the lines of armour, following the shape of the curved “peascod” belly down into a point, just like a breastplate. For anyone familiar with the codpiece, you’ll know these weren’t the only things 16th-century men were padding…

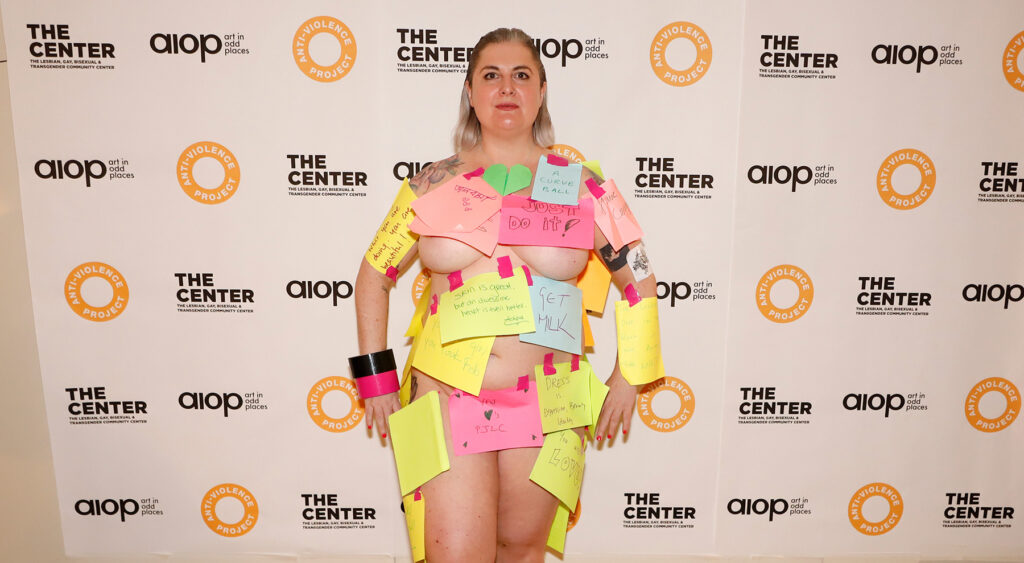

Vanessa Fairfax-Woods took the premise of padding and sculpting flesh and turned it completely inside out with her incredible work, The F Word. In previous centuries, flesh didn’t need to be toned, it was manipulated and sculpted by the garments worn – smoothened, cinched, impossibly flattened, or hidden beneath farthingales, bumrolls, stomachers and stays. The F Word enhanced and distorted Fairfax-Woods’ body’s natural shape, with jutting pleated flourishes, cut-outs and flowing folds, reminiscent of toga-clad Greek and Roman sculptures. The contrast with her costume for the Paper Dress Ball – her body unadorned but for the gradually accumulating post-its applied during the course of the evening – might be the piece(s) that has stuck with me the most from this year’s Art in Odd Places. For a fashion historian writing about a festival of dress, to come away thinking more about the naked body might seem absurd. But Art in Odd Places made me reflect on my own body, on my self-esteem and then made me more determined than ever to take up space with my clothing. To all of you, I say: wear the wild outfits! And to Art in Odd Places’ inimitable and tireless curator, Gretchen Vitamvas, I say: congratulations. Here’s to pulling focus.

. . .

Fashion historian and old master paintings specialist at Christie’s New York Jonquil O’Reilly brings portraits from the English Renaissance to life, breaking down the ostentatious ensembles worn by members of the Tudor court, decoding the symbolism in their sartorial choices, and explaining the material and function of these elaborate garments and adornments.

O’Reilly writes and lectures on historical fashion as a means of contextualizing old master paintings, making them more approachable for new audiences. As “The Costumist,” she contributed regularly to Harper’s Bazaar online and has given fashion lectures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Royal Academy, Chatsworth House, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Lobkowicz Palace at Prague Castle.